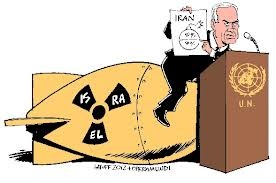

With the Western war machine stopped from liberating bombing/invading Syria for now, hawkish eyes are turning to Iran. We are told by our media that they are trying to develop a nuclear bomb, which they aren’t but that doesn’t stop Israel et al from pushing the narrative. If Team America attempted to intervene in Syria it would have invoked Iran to intersect due to the defence pact they have with the Syrians. Now cue the Netanyahu and Obomber memes of Iran having a bomb….a country to have invaded no-one in over 300 years, oh the irony. Courtesy of NewLeftProject:

Iran poses a far more serious threat to the U.S. than its disputed nuclear aspirations. Over the last few years, Iran has unleashed a weapon of mass destruction of a very different kind, one that directly challenges a key underpinning of American hegemony: the U.S. dollar as the exclusive global currency for all oil transactions.

It began in 2005, when Iran announced it would form its own International Oil Bourse (IOB), the first phase of which opened in 2008. The IOB is an international exchange that allows international oil, gas, and petroleum products to be traded using a basket of currencies other than the U.S. dollar. Then in November 2007 at a major OPEC meeting, Iran’s President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad called for a “credible and good currency to take over U.S. dollar’s role and to serve oil trades”. He also called the dollar “a worthless piece of paper.” The following month, Iran—consistently ranked as either the third or fourth biggest oil producer in the world—announced that it had requested all payments for its oil be made in currencies other than dollars.

The latest round of U.S. sanctions targets countries that do business with Iran’s Central Bank, which, combined with the U.S. and EU oil embargoes, should in theory shut down Iran’s ability to export oil and thus force it to abandon its nuclear program by crippling its economy. But instead, Iran is successfully negotiating oil sales via accepting gold, individual national currencies like China’s renmimbi, and direct bartering.

China and India are by far the most significant players, with Russia playing a supporting role. China is Iran’s number one oil export market, followed by India. Both have been paying for at least part of their Iranian oil imports with gold, and according to the Financial Times, have also been paying in their own currencies, the Chinese renmimbi and Indian rupee.[1] As neither currency is easily convertible as international currency, they will be used to pay for Chinese and Indian imports. And on 22 June, Russian media reported that China imported almost 524,000 barrels per day in May, a whopping 35% jump from the previous month.[2]

There is only so much the U.S. can do if China continues to do business with Iran. China holds $1 trillion dollars of U.S. debt, and the U.S. is utterly dependent on cheap Chinese manufacturing. Significantly, just as the newest and toughest round of U.S. sanctions kicked in at the start of July, Iran’s PressTV announced that China would be investing at least $20 billion to develop the north and south Azadegan and Yadavaran oil fields which will produce 700,000 barrels per day. Azadegan is estimated to contain 42 billion barrels, making it one of the world’s largest oil deposits.[3]

America has more leverage with India, but with the “BRICs”—Brazil, Russia, India and China—showing increasing solidarity in dealing with the U.S. and Europe, U.S. options are still limited. In January Bloomberg reported that all Russian trade with Iran was being conducted in Russian rubles and Iranian rials, and not U.S. dollars.[4]

Instead of shunning Iran as per U.S. dictate, many countries are simply finding ways around the sanctions. On 20 June, ten days before the tougher sanctions came into place, Turkey and Iran announced that they would trade in their local currencies and bypass dollar transactions.[5] Turkey is Iran’s fifth largest oil market. Local currency that has little convertible value internationally is one thing. Gold is quite another, and on 9 July, the Financial Times reported that Turkey had paid $1.4 bn in gold for Iranian oil in May.[6]

In January, Fars, Iran’s state run media, reported that all Iranian trade with Japan, Iran’s third biggest oil importer, was dollar free.[7] The Tehran Times reported in July that South Korea, Iran’s fourth largest oil market, was considering bartering manufactured goods for Iranian oil,[8] and Reuters reported that Indonesia was considering doing the same for palm oil.[9] Sri Lanka and Vietnam were also considering dropping the dollar to guarantee ongoing access to Iranian oil.[10]

How the Petrodollar System Works

In a nutshell, any country that wants to purchase oil from an oil producing country has to do so in U.S. dollars. This is a long standing agreement within all oil exporting nations, aka OPEC, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries. The UK for example, cannot simply buy oil from Saudi Arabia by exchanging British pounds. Instead, the UK must exchange its pounds for U.S. dollars. The major exception at present is, of course, Iran.

This means that every country in the world that imports oil—which is the vast majority of the world’s nations—has to have immense quantities of dollars in reserve. These dollars of course are not hidden under the proverbial national mattress. They are invested. And because they are U.S. dollars, they are invested in U.S. Treasury bills and other interest bearing securities that can be easily converted to purchase dollar-priced commodities like oil. This is what has allowed the U.S. to run up trillions of dollars of debt: the rest of the world simply buys up that debt in the form of U.S. interest bearing securities.

The flip-side of this are the countries that produce and export oil, in particular Saudi Arabia and the other Arab producers. The only way the system can possibly work is if oil producers refuse to accept anything other than U.S. dollars as payment for their oil. This they have done since the Nixon Administration’s manipulation of the OPEC oil crisis in the mid-1970’s, which succeeded in getting Saudi Arabia, traditionally the world’s dominant producer, to agree to accept only dollars for oil. The Saudis used their influence to get the rest of OPEC to agree as well. In return, the U.S. offered to militarily defend not so much Saudi Arabia, but the horrifically repressive monarchy that ruled it.[11]

But there was a kicker: Nixon and his Secretary of State Henry Kissinger also got the Saudis to agree to invest their mega oil profits in the U.S. economy. In addition to buying interest bearing U.S. government securities, the Saudis also invested in New York banks. Because the OPEC oil embargo had quadrupled global oil prices, the Saudis and other Arab producers suddenly had a great deal of money to invest. The money parked in those New York banks then became available to be loaned to the rest of the world, which faced major financial crises due to—yes, you guessed it—the sudden quadrupling of oil prices. By the year 2000 and Iraq’s dramatic switch to selling Iraq’s oil in euros, Saudi Arabia had recycled as much as $1 trillion, primarily in the United States. Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates recycled $200–300 billion.[12] And because those loans were in U.S. dollars, they had to be paid back in U.S. dollars. When U.S. interest rates skyrocketed to 21 percent in the early 1980’s, interest on the loans also skyrocketed. This in turn precipitated a third world debt crisis, which was mercilessly exploited by Wall Street and the U.S. In this case, the exploitation came in the form of requiring countries to “structurally adjust” their economies along neoliberal lines in return for World Bank and IMF bailout loans. By 2009, the total debt owed on these bailouts and other loans was an astounding $3.7 trillion. In 2008, they paid over $602 billion servicing these debts to rich countries, primarily the United States.[13] From 1980 to 2004, they paid an estimated $4.6 trillion.[14]

The history of how this came about is fascinating, and I discuss it in detail in Making the World Safe for Capitalism. The short version is that from the 1944 Bretton Woods agreement which set up the International Monetary Fund and the precursors to the World Bank and World Trade Organisation, the dollar was accepted as the international currency for all trade. Crucially though, the dollar was backed up by gold, which was fixed at $35 an ounce. This meant the U.S. had to have enough gold on hand to back up any and all dollars it printed.

Faced with escalating costs from the Vietnam War, in the early 1970s Nixon abandoned the gold standard and replaced it with the petrodollar system described above. Almost simultaneously, he abolished the IMF’s international capital constraints on American domestic banks, which in turn allowed Saudi Arabia and other Arab producers to recycle their petrodollars in New York banks.

The petrodollar system, and U.S. ability to manipulate the dollar as the global reserve currency and hence global debt, has been the bedrock of American economic power. But since the global financial crisis, U.S. policy has been to keep interest rates extremely low to stimulate borrowing. This has meant that the rate of return on those interest bearing securities that the rest of the world has invested in to enable them to buy oil exclusively priced in dollars is also now extremely low. In other words, there is no longer any real financial incentive for the rest of the world to sell its oil in dollars. Nor, crucially, is there as much incentive for OPEC and staunch U.S. ally Saudi Arabia to continue to kowtow to the petrodollar recycling system. After all, the U.S. invaded Iraq and has now de facto control of enough oil production to render reliance on the Saudis potentially irrelevant. And thanks to decades of American military training and hardware procurement, the Saudi military certainly has the capacity to defend itself and even to project its power, as it exhibited last year by invading Bahrain to help suppress the uprising against the equally repressive Al Khalifa monarchy.

In October 2009, veteran Middle East correspondent Robert Fisk of Britain’s Independent newspaper broke the story that Gulf oil-producing countries, along with China, Russia, Japan and France, were planning a new system to replace the dollar as the de facto currency for global oil sales by 2018. The dollar would be replaced by a basket of different currencies including a yet-to-be-released new currency for the Gulf Co-operation Council countries of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, Qatar and Bahrain.[15] Other currencies would include the euro, the Chinese yuan [renmimbi] and Japanese yen. Gold would also be included in the mix. That long-term allies like Saudi Arabia and the other Arab Gulf states, along with Japan, were involved suggests that U.S. leadership is being seriously questioned, if not outright challenged.

U.S. Protection of Dollar Dominance

By accepting and encouraging countries to pay for its oil in currencies other than the U.S. dollar, Iran has deliberately taken the same action that, I argue in Making the World Safe for Capitalism, led directly to the U.S. invasion of Iraq. In September 2000, Saddam Hussein announced that Iraq would no longer accept the “currency of its enemy”, the U.S. dollar, and from that time onwards any country that wanted to purchase oil from Iraq would have to do so in euros. I further argue that the motivation for the United States’ invasion of Iraq was to eliminate the threats a post-U.N. sanctions Iraq posed to the key underpinnings of American economic hegemony, and to install a pro-U.S. client state and permanent American military presence in the region. The book examines how a post-U.N. sanctions Iraq either directly threatened the ongoing success of American economic power, or provided enormous opportunities to extend it.

All the same considerations are in play with Iran, starting with Iran’s direct threat to the dollar as the dominant global reserve currency. But that is just one aspect of the much larger issue: that Iran openly defies U.S. neoliberal hegemony. Like Iraq pre-invasion, Iran is not a member of the WTO, has not had any dealings with the IMF since 1984, and does not have any debt with it or the World Bank. Like Iraq before it, and evidenced by China’s oil development contracts, the U.S. and its oil companies are cut out of any future oil development in Iran. Like a post-sanctions Iraq, Iran has the potential to be the dominant power in the region and to provide development assistance on a vastly different model to that imposed by the WTO, World Bank and IMF, against which so much of the Middle East is rebelling.

The U.S. has shot itself in the foot. Far from isolating Iran, the sanctions are potentially speeding up the demise of the dollar’s dominance by forcing Iran to explore alternative currencies. That so many other countries are so willing to support Iran in direct defiance of the sanctions is what the U.S. clearly bet against. It might end up as the biggest foreign policy blunder in American history. Either that, or yet another war.

Christopher Doran is the author of ‘Making the World Safe for Capitalism: How Iraq Threatened the US Economic Empire and had to be Destroyed’. A long-time activist and writer, he teaches in the department of labor studies at Indiana University, Bloomington, and the department of Political Sociology at Indiana University, Columbus.